With series such as The Cars or Concord, Wolfgang Tillmans continues that redefinition of the linguistic practice of photography that began since its inception in the early 1990s.

Outlining a new kind of subjectivity capable of messing up and questioning the values and hierarchies of this newborn language, Tillmans’ work fits into the history of the evolution of photographic language like a fresh and disruptive wind , capable of so much lightening the photographic behavior as to give it the truth of an experiential gesture and instinct that, if at its beginnings in the early nineties could be provocative, on closer inspection, considering the course taken by photography also thanks to the implementation brought about by the digital revolution, today appears to have been far-sighted.

If we look at the linguistic investigation conducted by Wolfgang Tillmans in series such as The Cars or Concord we can easily understand how the author of these taxonomic and insistent recordings was able to discuss with extraordinary simplicity the very foundations of linguistic practices typical of traditional photography to replace these with postural behavior in which technical and formal dictates are serenely distorted.

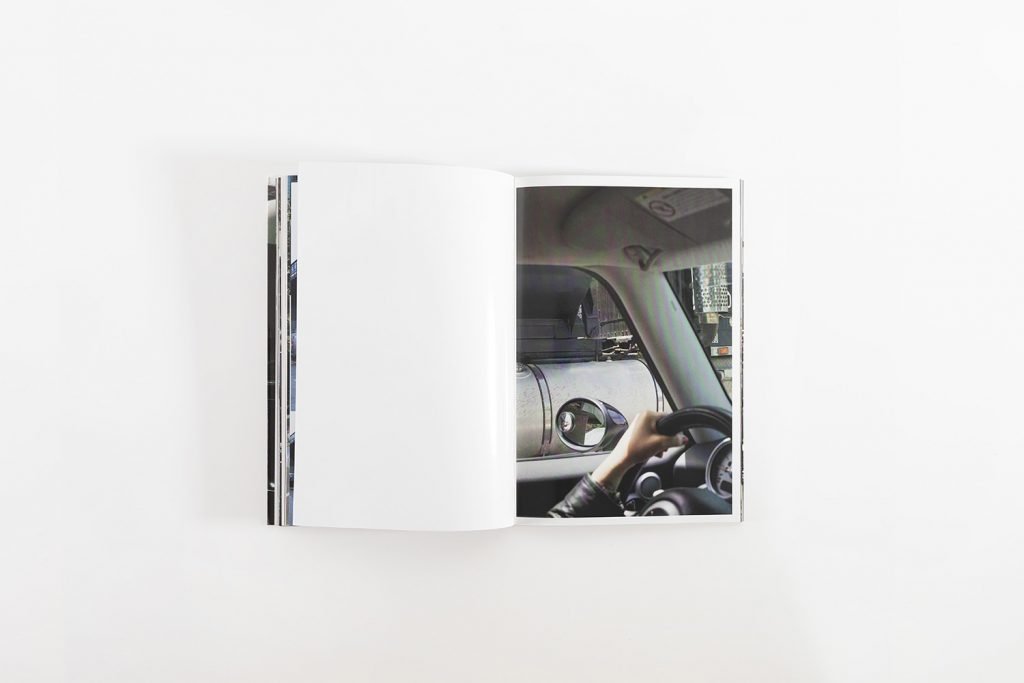

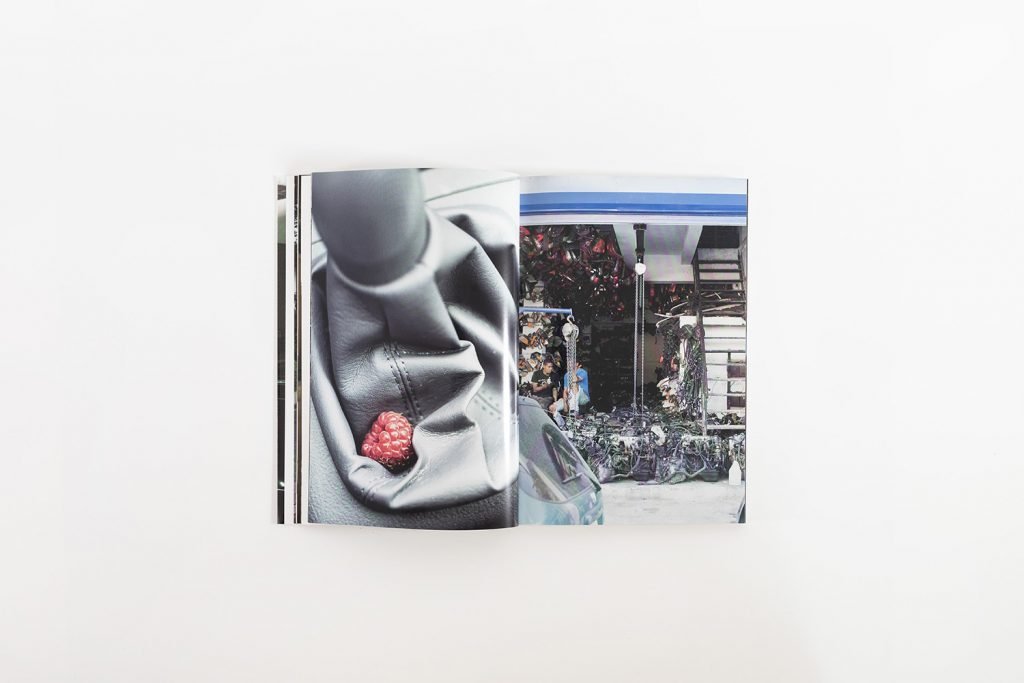

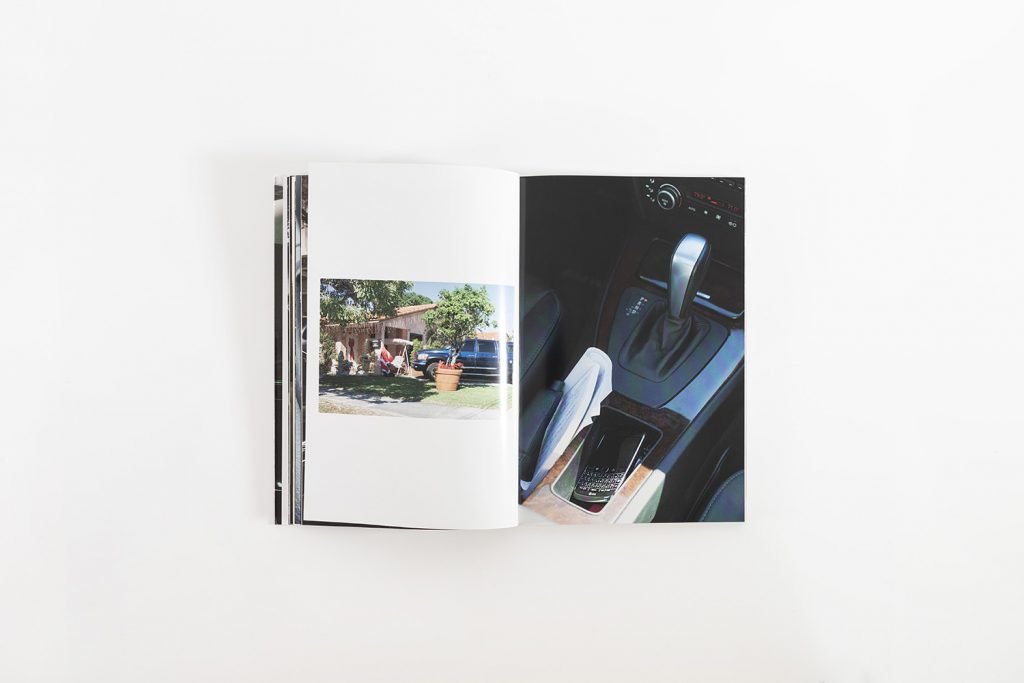

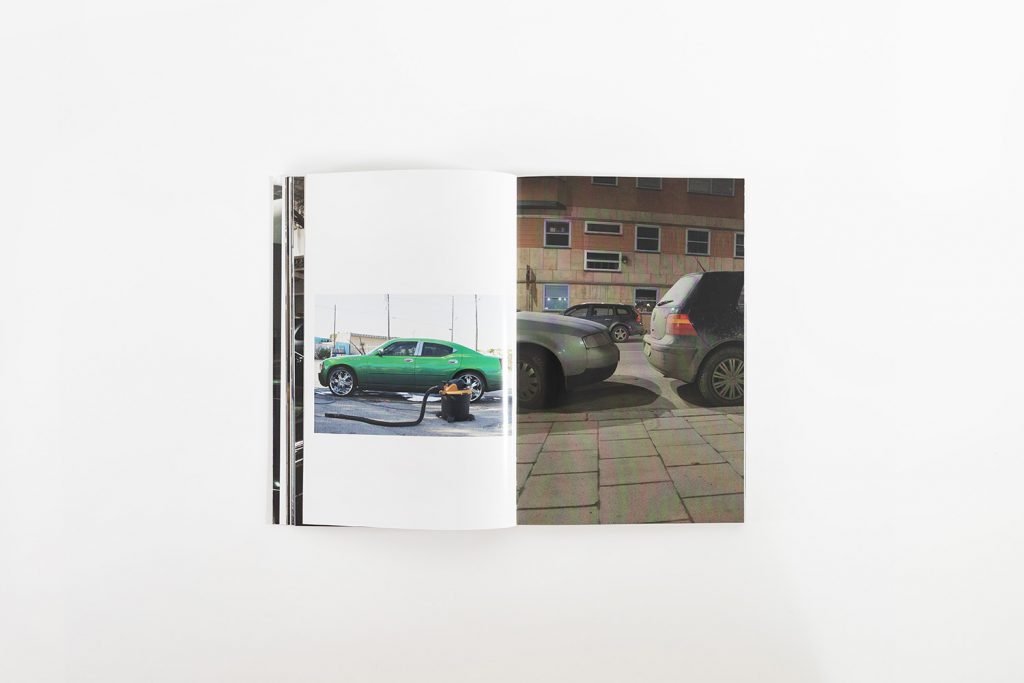

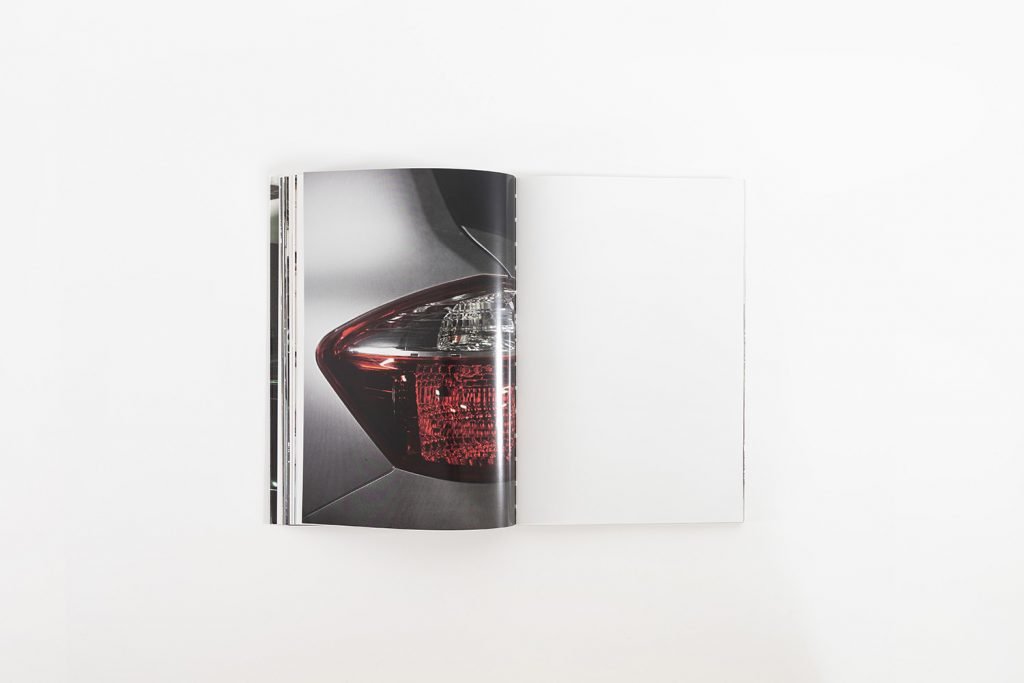

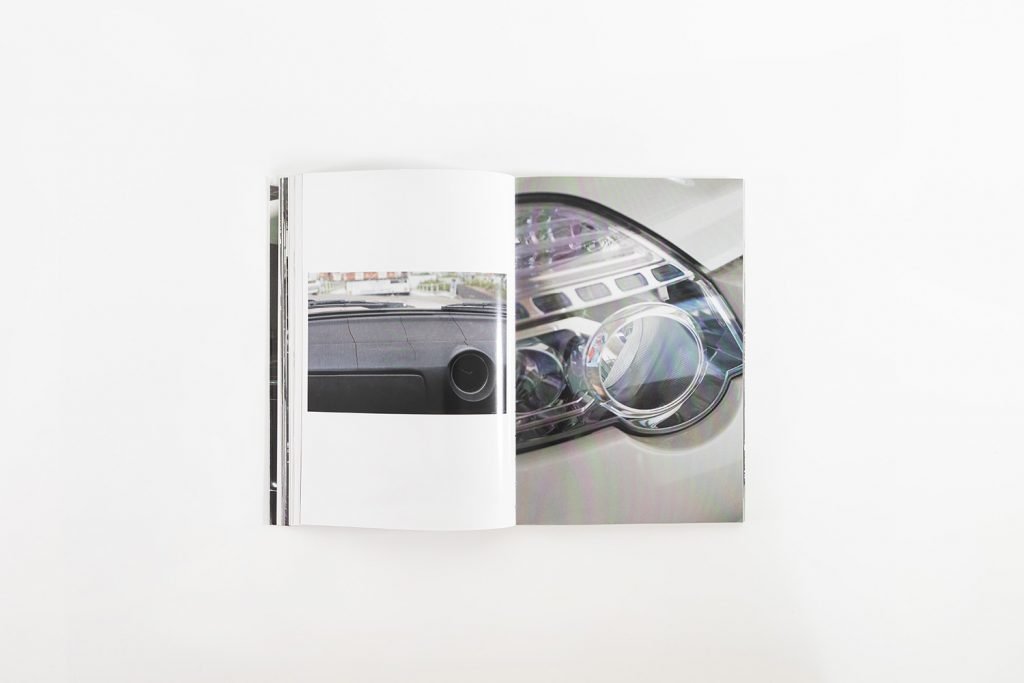

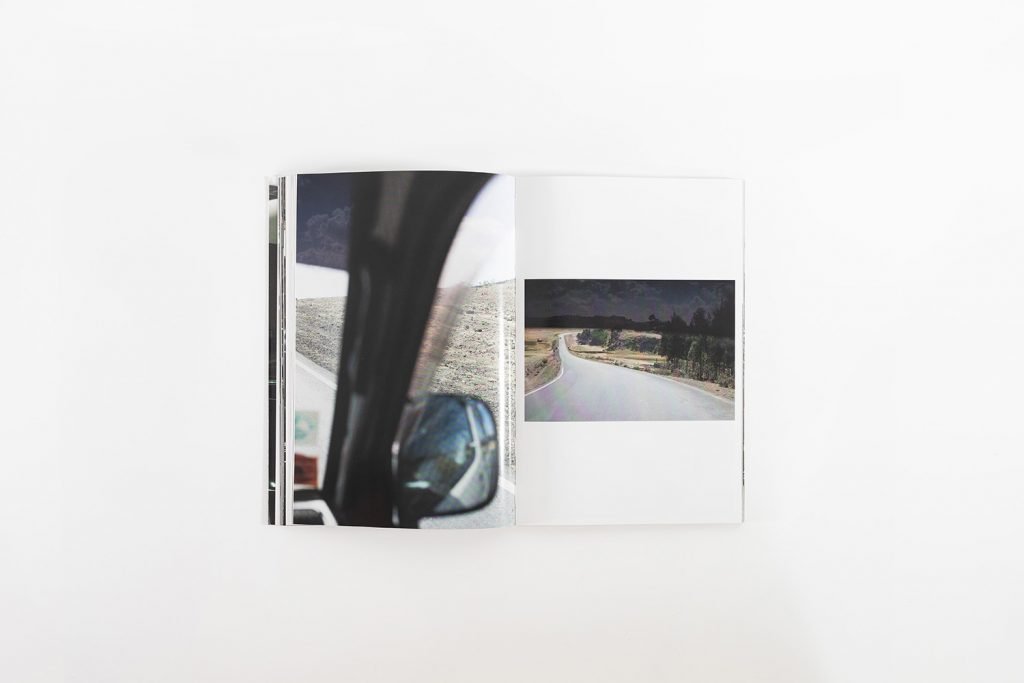

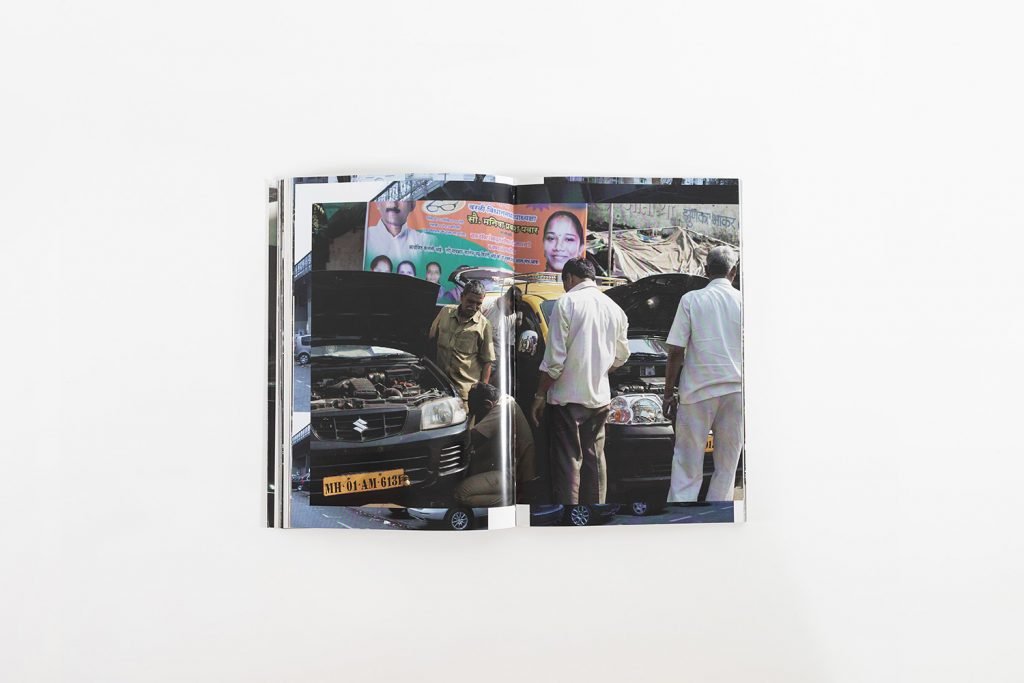

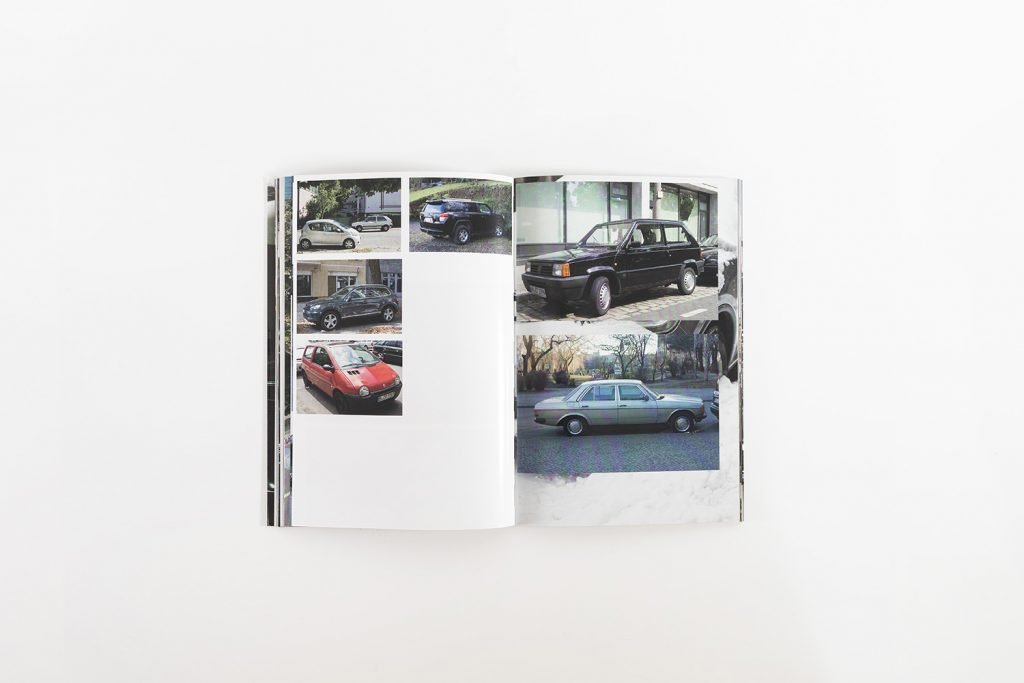

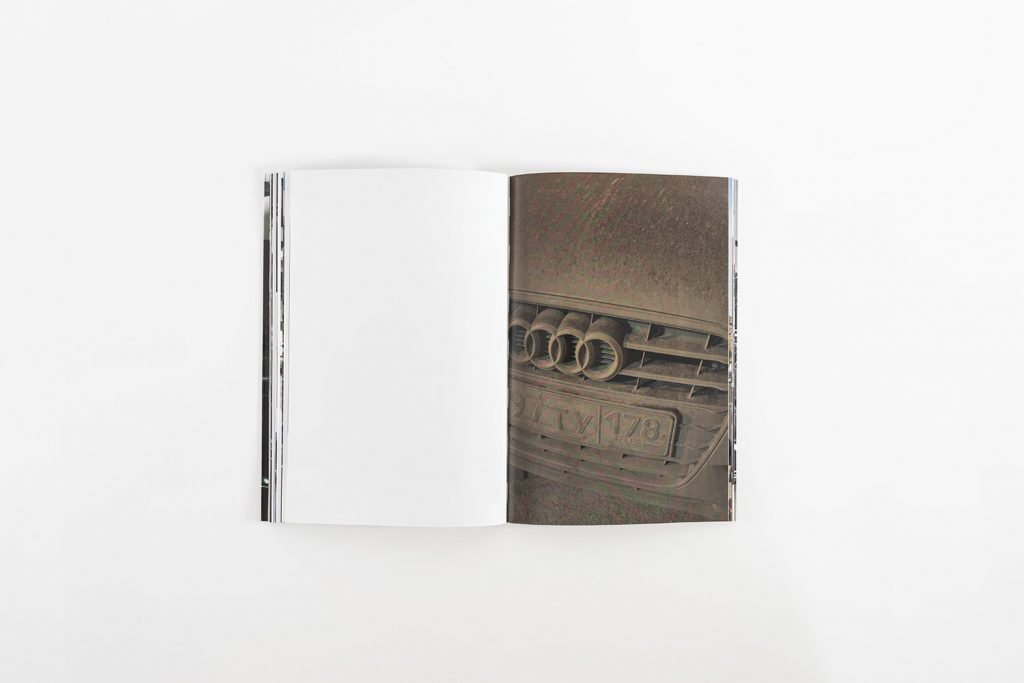

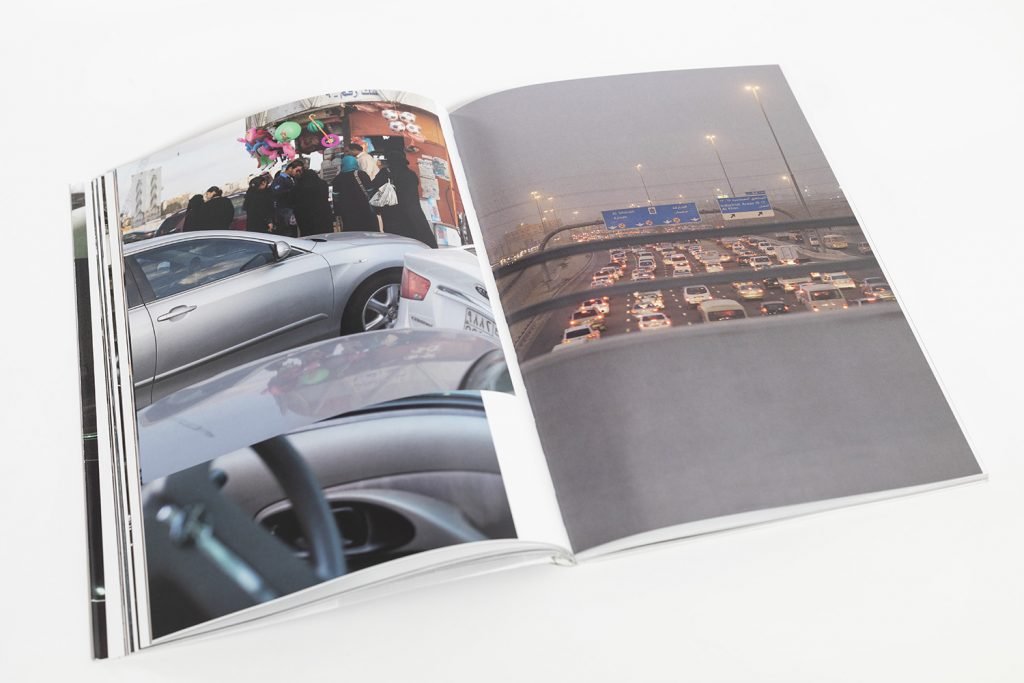

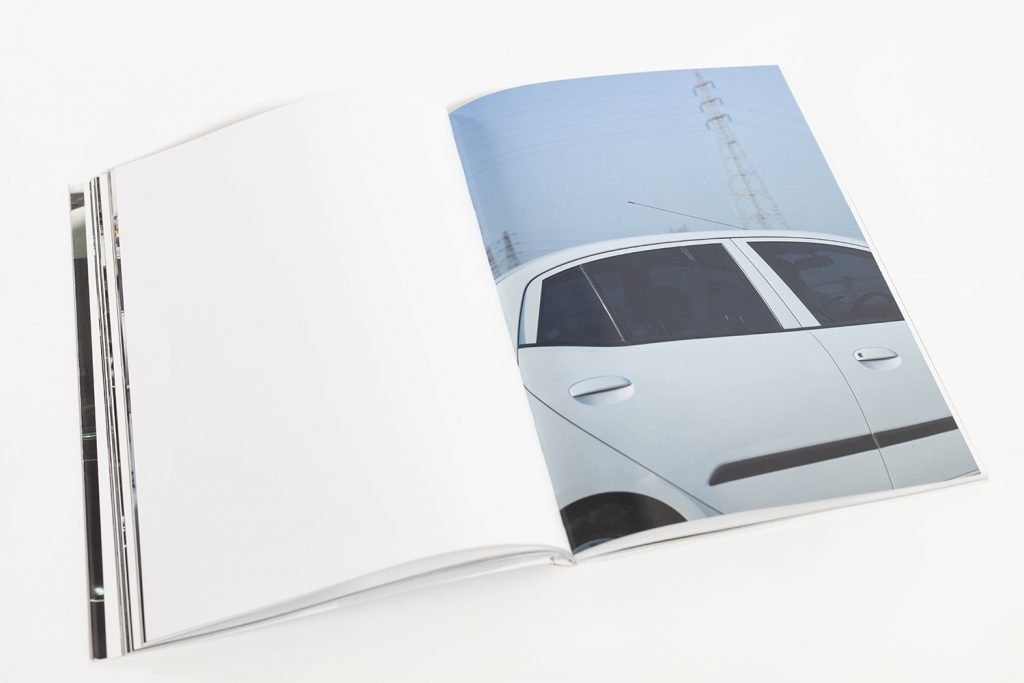

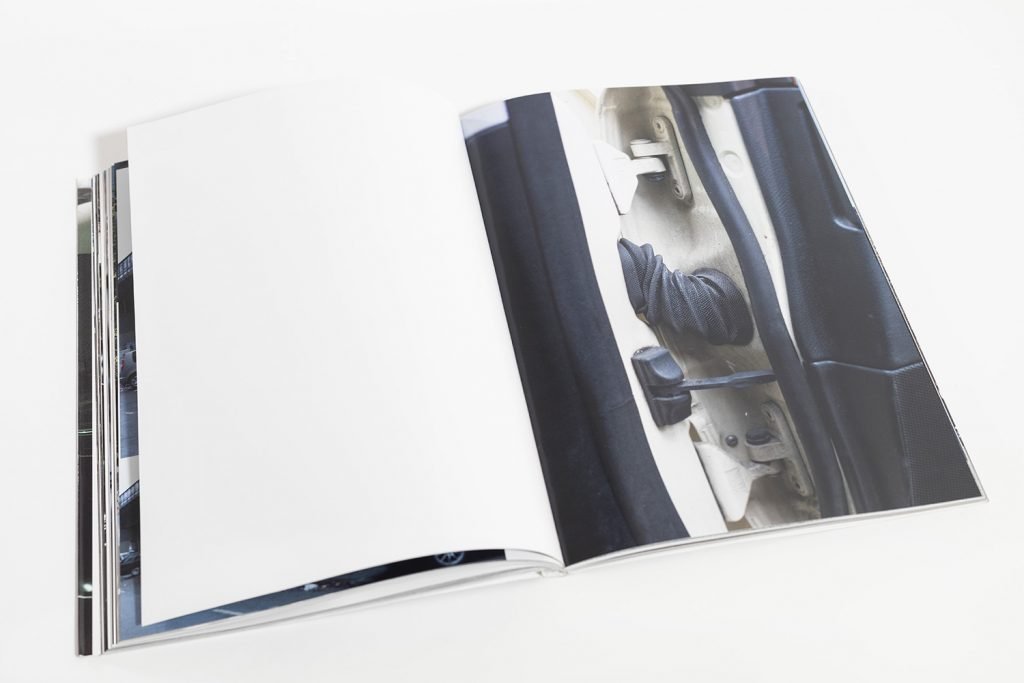

A change in the forms of photography that allows a representation in which the experience and subjectivity of the observation itself is placed at its center. A look and freely manage the gaze that, if in a series like Concord does not fail to report an intimate, almost melancholy feeling, in other works such as The Cars, throws the viewer into a nervous sequence of repetitive and fast images that tell the story of the author and his gaze in an alarmed and critical observation of that daily hyper-presence of cars that has redefined the very structure of the habitat of every day.

A reconfiguration of the everyday landscape that with sensible farsightedness was already denounced in extraordinary works such as Ballard’s Crash, which later became the subject of an extraordinary film directed by David Cronemberg and which in Tillmans finds the strength to become lean and bulimic observation.

“Cars are everywhere,” the photographer says. “Their sheer number is the most crazy thing about them. They appear in our lives with excessive omnipresence. In their volume cars intrude upon public space, and the way they occupy streets and open areas is rarely challenged.”

And then…

“Virtually wherever there are people, there are cars and they are visually intermingling in whatever we see,” Tillmans points out. “We are looking at the world from a car and cars are in the foreground, the background or in between of what is in our view.”

The repeated images of cars portrayed in a simple and typical street view, not in an accident or in an extreme and exasperating traffic jam as in Crash, but simply constantly present, make the exploratory journey on this rhythmic visual archive, cadenced in an equality. Almost as if the individual images can only be enjoyed and impressed by the observer only in relation to the expression and choral effect of the whole. An ambiguous tribute to the amount of time we spend around, observing or using the car.

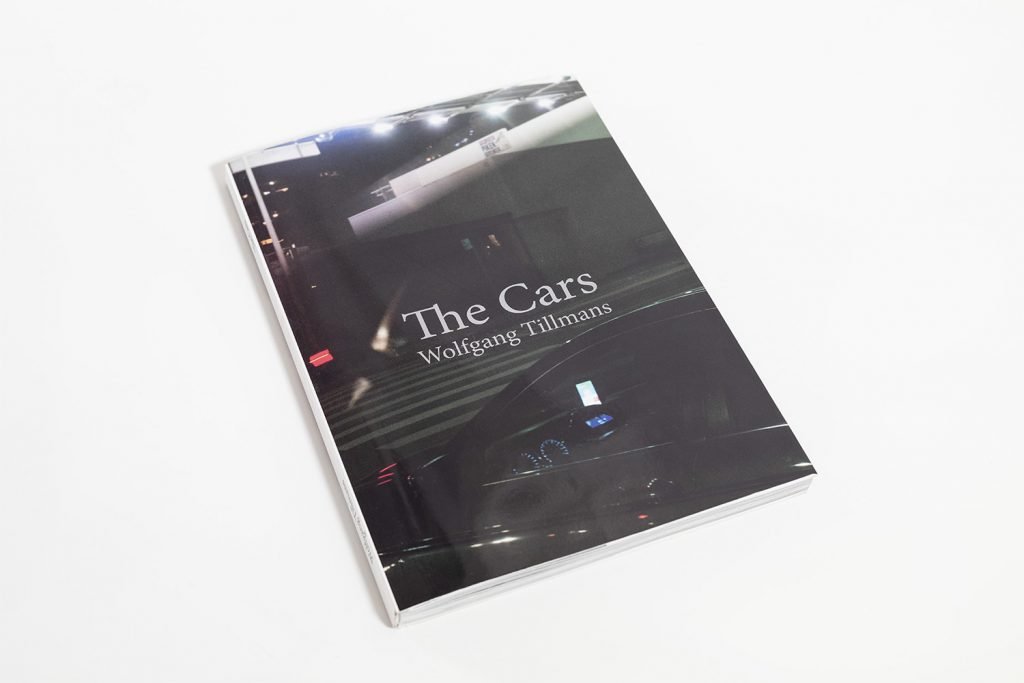

The Cars

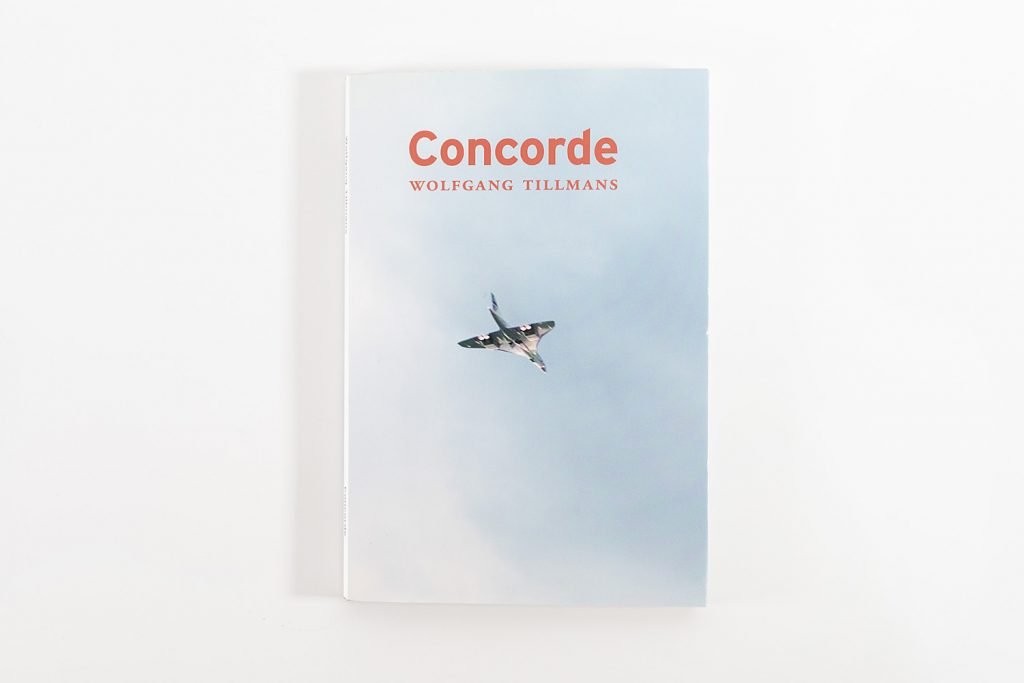

Concorde

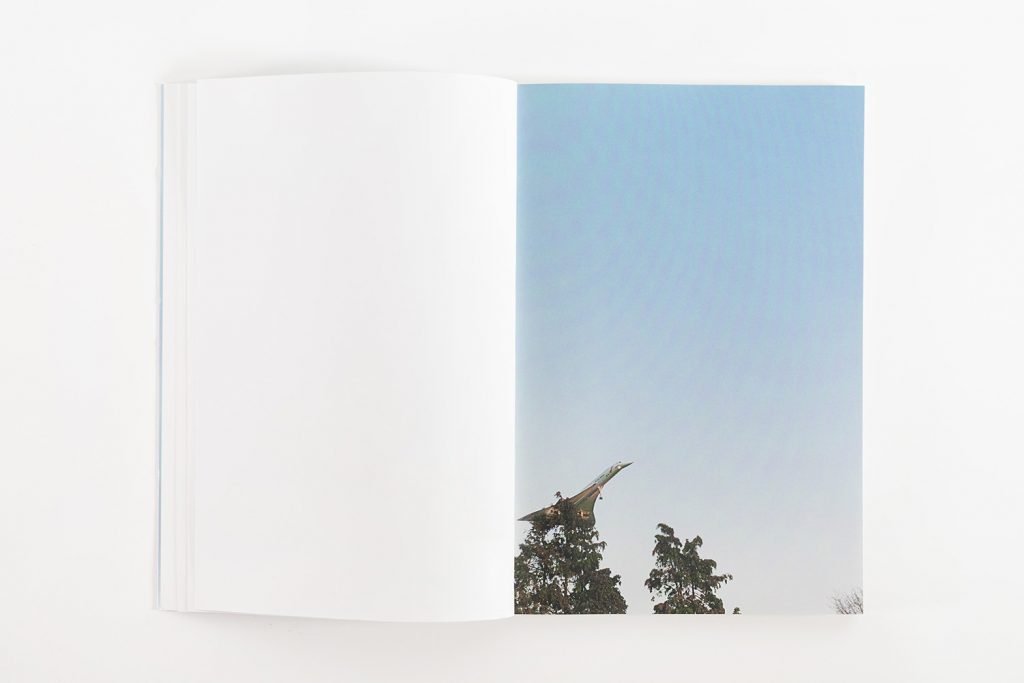

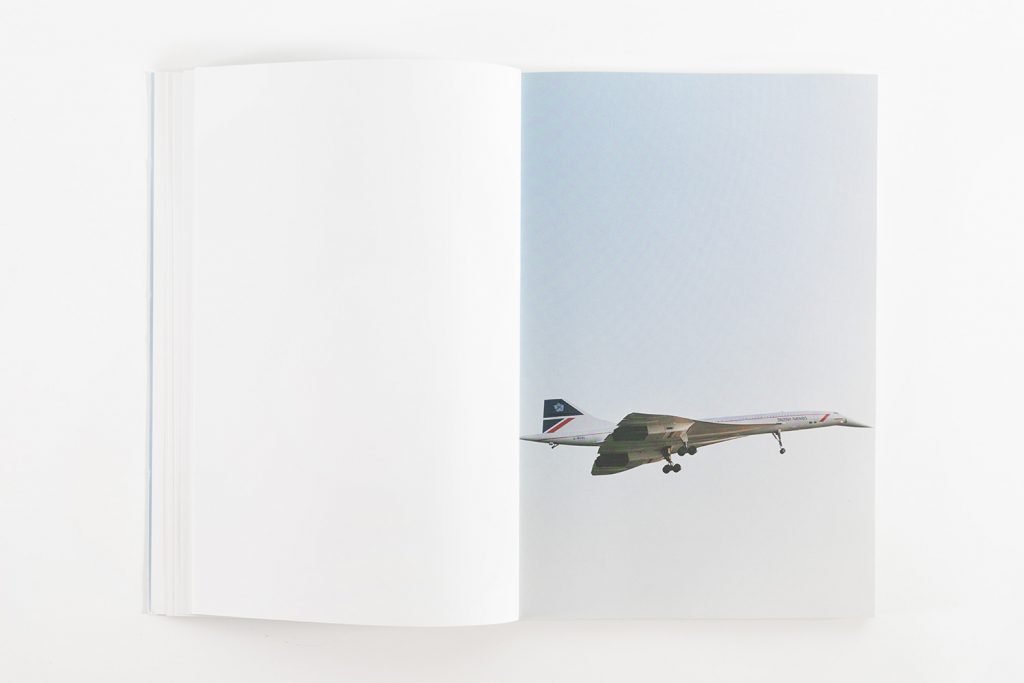

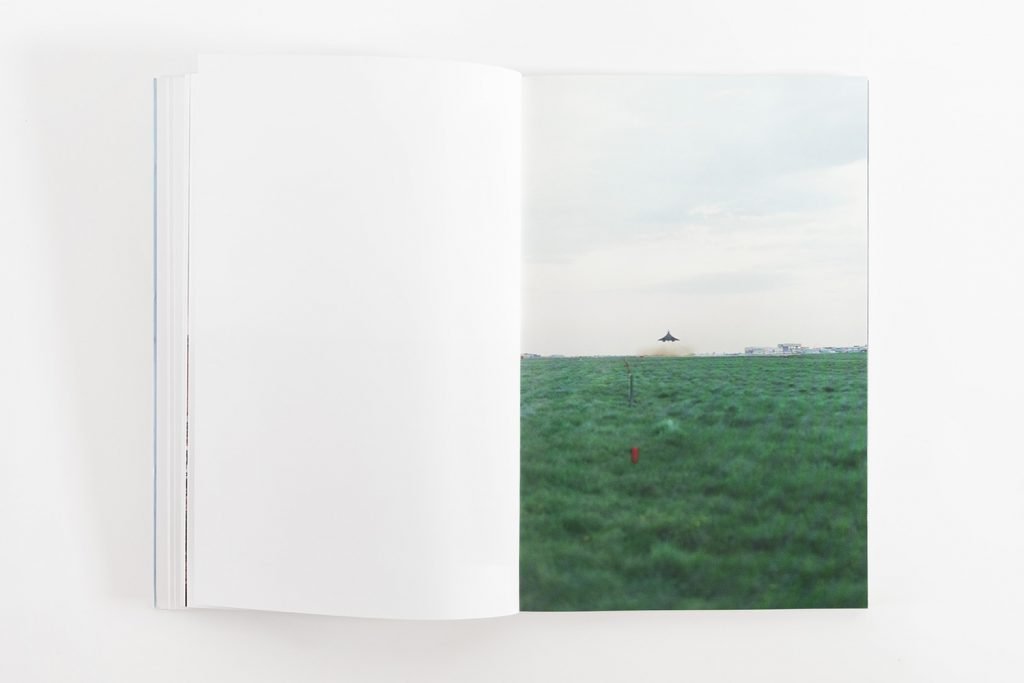

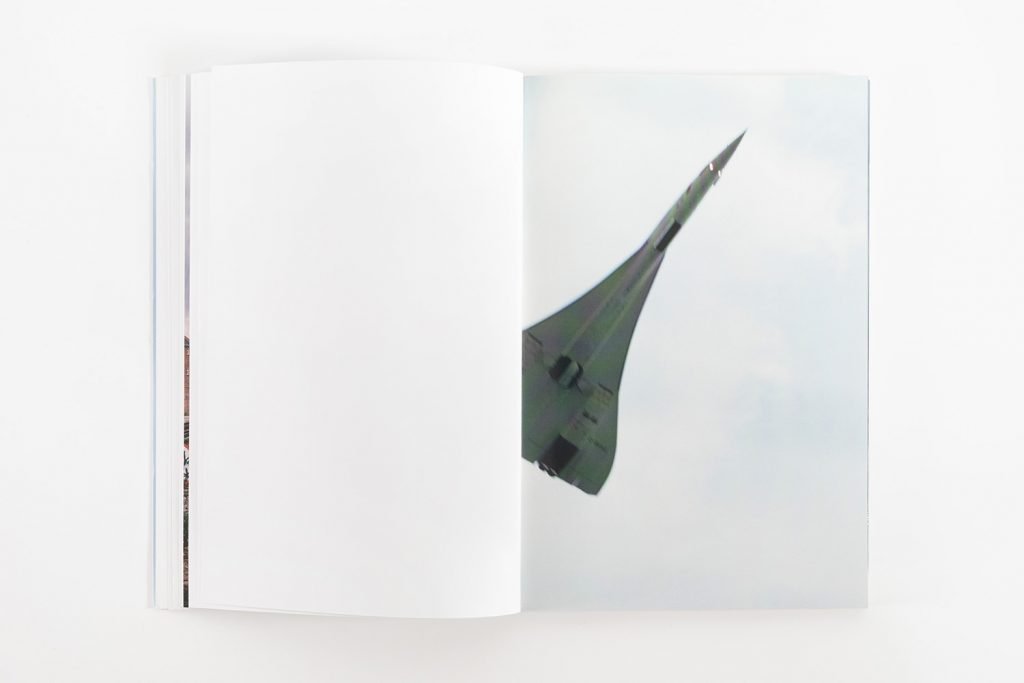

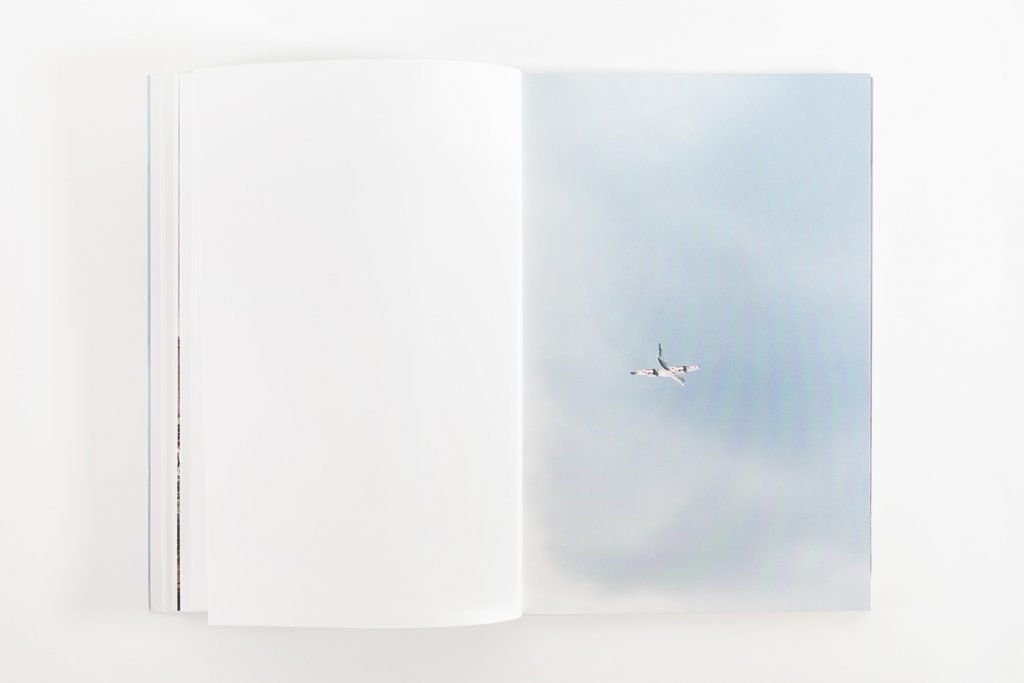

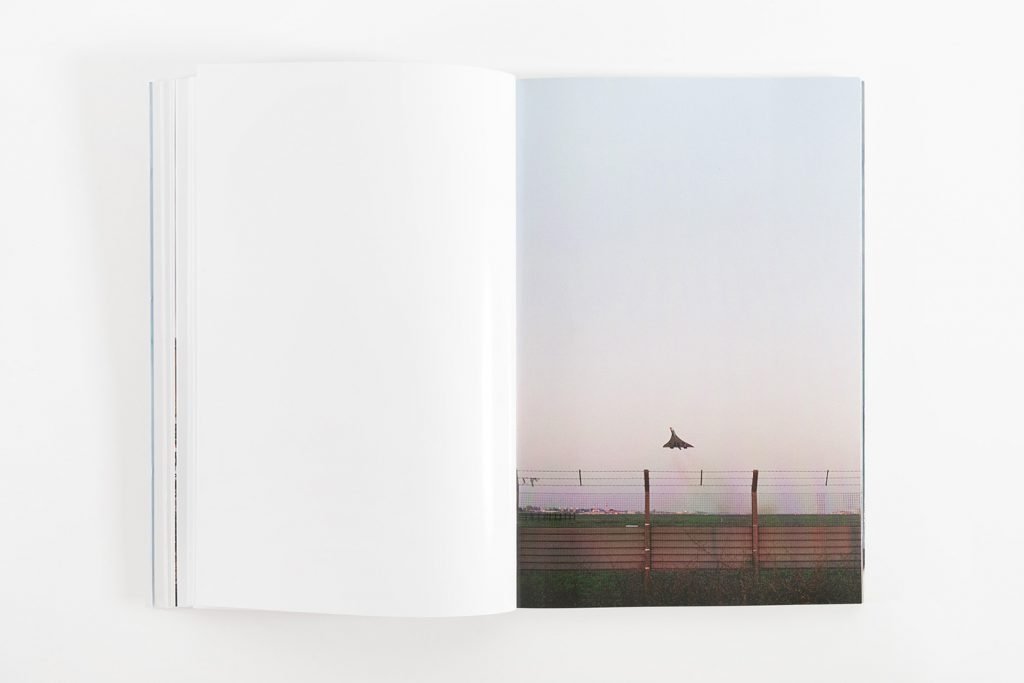

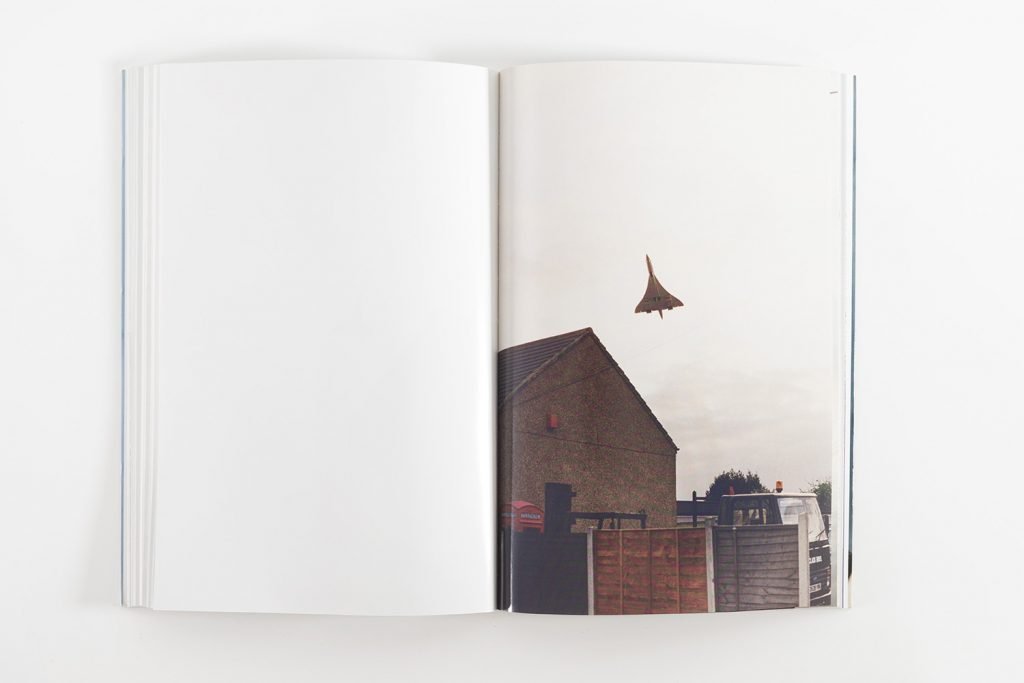

Concorde Grid is a series of fifty-six color photographs of equal size that are displayed in a grid four rows high and fourteen columns wide. The series, shot as part of a commission for the Chisenhale Gallery, (London), on the occasion of I Didn’t Inhale, (Tillmans’ solo exhibition in 1997) was shot at a number of sites in and around London.

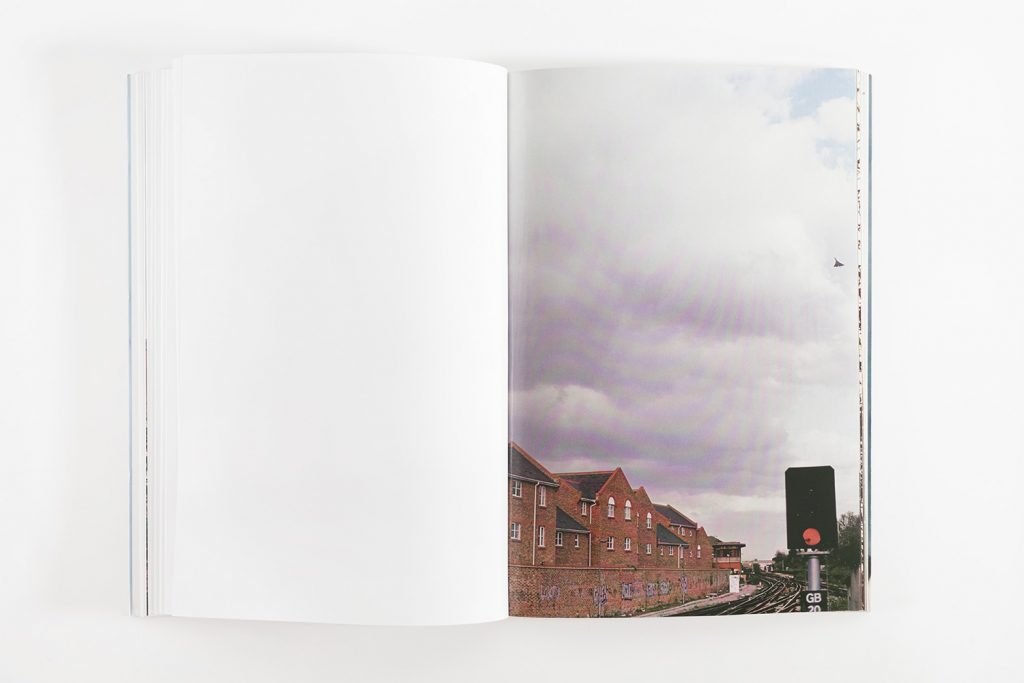

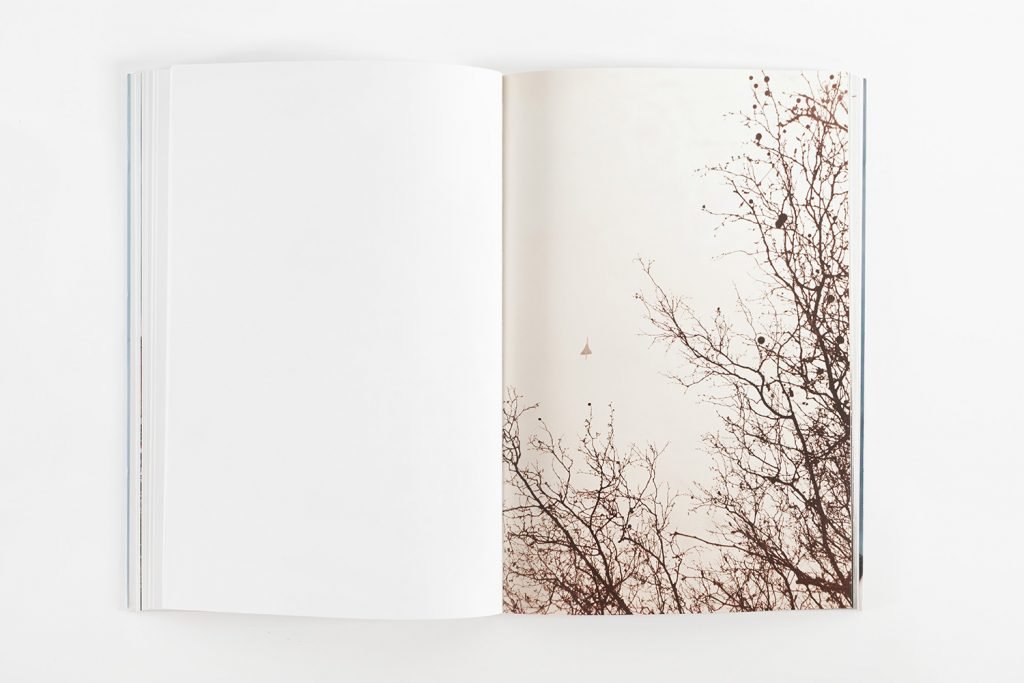

Several photographs of the plane landing and taking off from the airport were taken looking through the security fence, near the Heathrow airport perimeter fence which is included in the image as a blurry outline, while other photographs were taken from points of views such as suburban railroad tracks, roads near the airport, a yard containing parked trucks, and an open Municipality.

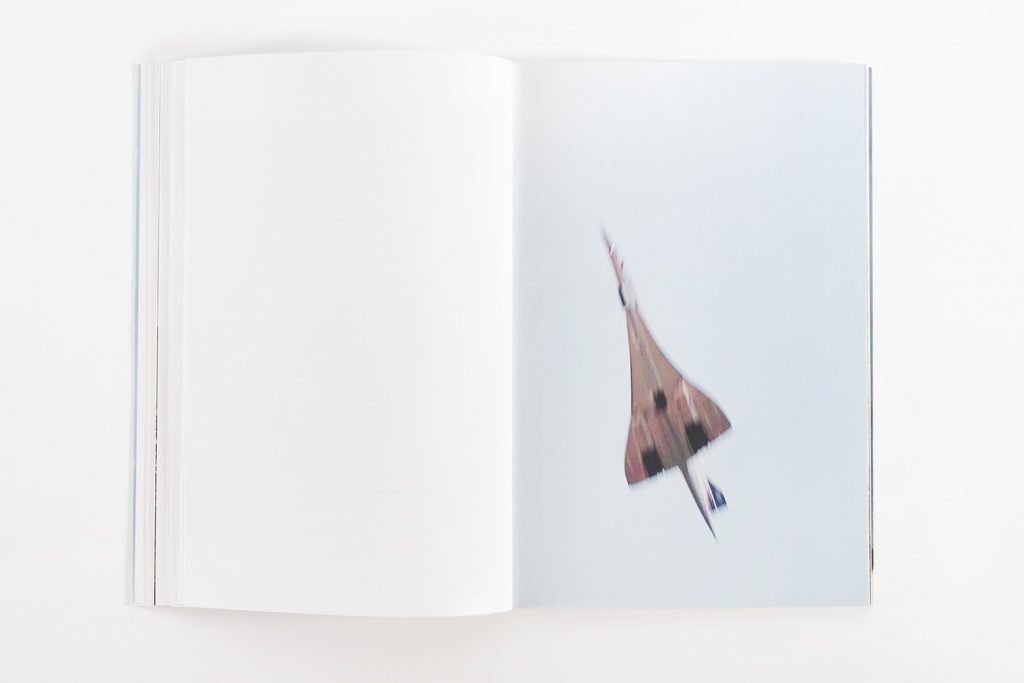

The plane depicted in different scales and seen from a wide variety of angles recurs in the representation giving image after image a different impression.

The project, characterized by an obsessive and recurrent reproduction of the same subject, takes on the character of a monitoring or a recording not unlike that of a birdwatcher.

The author writes:

“Concorde is perhaps the last example of a techno-utopian invention from the sixties still to be operating and fully functioning today. Its futuristic shape, speed and ear-numbing thunder grabs people’s imagination today as much as it did when it first took off in 1969. It’s an environmental nightmare conceived in 1962 when technology and progress was the answer to everything and the sky was no longer a limit … For the chosen few, flying Concorde is apparently a glamorous but cramped and slightly boring routine whilst to watch it in the air, landing or taking-off is a strange and free spectacle, a super modern anachronism and an image of the desire to overcome time and distance through technology.”

Although not devoid of social attention, Tillmans’ visual investigation in Concorde describes something more than the mere objectivity of the scene. In the work of facts, the formal choices made in the shooting of the subject tell us both this and (as reported above in the words of the same author) the experience and the show that the Concorde, as an event, produces.

Reasoning a vision that sees the postural approach to the subject represented, the author captures and collects the sensation of this, giving life to a set of visions in which it is possible to intercept the emotional oscillation of the author himself who, now amazed, now melancholic, now distant, seems to look at things to hear his own noise.